How many Beats were there? That’s right. About four. Allen, Jack, William (who didn’t like being called a ‘beat’) and maybe Lucien that guy from the film with Daniel Radcliffe doing his best Americanish.

Wait no. That’s bollocks.

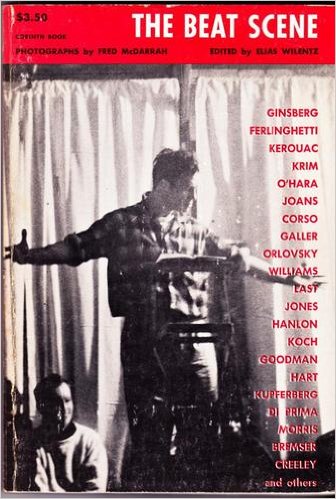

According to ‘THE BEAT SCENE’, published 1960 by Corinth Books, there were over 40 figures pertaining to the ‘Beat’ title. Not only that but women (shock!), black people (hor– oh, wait), plus bonus old age pensioners.

In one chapter Albert Saijo, a Japanese-American poet and translator, collaborates with Jack Kerouac and Lew Welch while a diligent Gloria–in keeping with the pop view of suppressed female beats–types their orations on a typewriter. As a boy Saijo was interned in an American-Japanese relocation centre during the ‘Yellow Peril‘ paranoia of WWII, but the placation of racial guilt doesn’t soften the chapter’s misogynistic vibe. Lines like ‘what am I, a girl?’ grate nowadays, never mind to the typist sat beside them. Gloria is even berated in the poem itself, a self-reflexive line that is unfortunate,

Thou irk’st but for gain

Gloria you aren’t getting the punctuation

Damn it, Gloria, god forbid you contribute to this poetic ego-stroking session. Gloria has the ultimate power over this typescript however–may be she planted herself there–we can only hope. You go, Gloria.

Female voices are heard over the angsty male clamour in the book, particularly from Diane DiPrima and Barbara Ellen. Ellen’s sole poem ‘Boris Oblesow’ seems a parody of scatological beat poems but the title links the near-extradition of an adopted Russian orphan by an American tank commander to the disillusionment of post-war American identity. DiPrima gets a mere extract from her longer poem ‘Necrophilia’, and Brigid Murnaghan includes a single poem. The feeling remains that it was hard to be considered a ‘beat’ woman.

Ted Joans’ contributions are the best reads in the book. He is the subject of a collection of fantastic shots by Fred McDarrah who provides all photography for the book, and Joans appears to be an eccentric: cowboy chaps in one photo, beret and cigarette in another. A whole series of photographs follow Joans at his ‘biannual birthday party’. He went on to publish collections such as ‘Teducation’ and ‘Afrodisia’ and there’s an equally playful and edgy tone in Joans’ poetry. He provides some of the best visuals and poetry:

to publish collections such as ‘Teducation’ and ‘Afrodisia’ and there’s an equally playful and edgy tone in Joans’ poetry. He provides some of the best visuals and poetry:

Let’s play something. Let’s play some-

thing horrible. You be Hitler and you

be Mussolini and you be Stalin and

you be Tojo, and you be Strijdom of

South Africa and I’ll be Gov. Faubus

Wow! What a cast of devils! Yeah,

let’s play that.

Casting a long shadow is the not so fantastic LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka) an African-American poet known for controversy. In 1960 there were still five years before Jones would write a highly homophobic and minsogynst tract against white people in general. Another 41 years later Jones, now Baraka, wrote a poem about 9/11, blaming Israel with no apparent evidence: a rather strange man with a penchant for pasting large penises on the cover of his notebooks–probably his best contribution to the beats.

Another blog has noted this book as ‘a good primer’ for the beat scene in its entirety, and I would agree. Once the beats were galvanised by popular culture in the caricatures of exploitation film, the cream of the crop were immortalised by the larger publishers, leaving the rest to become the marginalised voices of the marginalised voices. It needs a new run in its exact 1960 formatting, because this book is 56 years old now and it feels modern in 2016.*

*My copy bought at Bookwise, Nottingham is inscribed by the former owner ‘Mark Hawkins, Hackney 1960’, but more interestingly has a typewritten name on the reverse of the front cover reading ‘LEE THE AGENT’. As said before, Burroughs’ didn’t like the beats but is it possible his NOVA Agent alter ego did?